Vector Operations:

- Addition

- Scalar multiplication

Linear Combinations (c, d, e $\in \mathbb{R}$):

- cu + dv

- cu + dv + ew

Properties of Dot Product:

- Distributive: $u^T(v + w) = u^Tv+u^Tw$

- Non-Associative: $u^T(v^Tw) \ne (u^Tv)^Tw$

- Commutative: $u^Tv = v^Tu$

Cosine Formula for Dot Product: $v^Tw = |v| . |w| . cos(θ)$ (note: cos(θ) = 0 when θ = 90°)

Length of a vector: $\left| \mathbf{v} \right| = \sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2 + v_3^2 + …}$

Matrix operations:

- Addition (both matrices should have the same dimensions)

- Scalar multiplication

- Transpose: mapping A ∈ $\mathbb{R}^{n \times m}$ to B ∈ $\mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ with $a_{ij} = b_{ji}$

- Trace: sum of all the elements along the diagonal

- Matrix multiplication (reminder: A∈$\mathbb{R}^{n \times m}$ and B∈$\mathbb{R}^{m \times k}$ then C=AB∈$\mathbb{R}^{n \times k}$)

Multiplication Properties:

- Distributivity: $(A +B)C = AC+BC$ and $A(C+D) =AC+AD$

- Associativity: $(AB)C = A(BC)$

- Non-commutative: $AB \ne BA$ (because of dimensions)

- Multiplication with the identity matrix results in the matrix itself

Properties of Transpose:

- $(A+B)^T =A^T +B^T$ and $(A - B)^T =A^T - B^T$

- $(AB)^T =B^TA^T$

Symmetric Matrices:

- $A^TB = B^TA$ if $A^TB$ is symmetric

Systems of Linear Equations Recap:

- $Ax = b$

- Gaussian Elimination

- Row Echelon/Reduced Row Echelon Form

A matrix is in row echelon form if

- all rows having only zero entries are at the bottom

- The pivot (the leftmost non-zero entry) of every non-zero row, called the pivot, is to the right of the leading entry of every row above

A matrix is in reduced row echelon form if:

- it is in row echelon form

- the leading entry in each nonzero row is 1 (called a leading one)

- each column containing a leading 1 has zeros in all its other entries (or in other words, above the pivot if condition one is achieved)

Properties of Determinants:

- Matrix must be square

- The determinant of the identity matrix is 1.

- The exchange of two rows multiplies the determinant by −1.

- Multiplying a row or a column by a number multiplies the determinant by this number.

- Adding a multiple of one row to another row does not change the determinant.

- If two rows of matrix A are equal, then $det(A) = 0$.

- A matrix with a row of zeros has $det(A) = 0$.

- If A is triangular then $det(A)$ is the product of diagonal entries.

- $det(AB) = det(A).det(B)$

- $det(A^T) = det(A)$

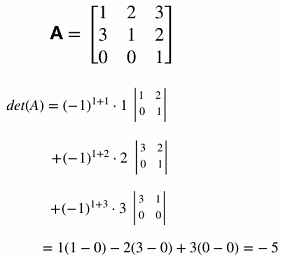

Laplace Expansion Example:

Invertibility:

- Matrix must be square

- If A is singular, then $det(A) = 0$. If A is invertible, then $det(A) \ne 0$.

- Can calculate the inverse using Gaussian Elimination

- $[A \vert I]$ -> $[I \vert A^-1]$

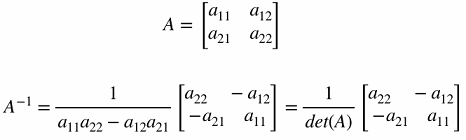

- Inverse for a 2x2:

Vector Spaces and Subspaces

A subspace is defined as a set of all vectors that can be created by taking linear combinations of some vectors or a set of vectors.

Formally, a subspace is the set of all vectors that satisfy the following conditions:

- Must be closed under addition and multiplication

- Must contain the zero vector

Note

A vector space needs to contain all linear combinations of its vectors.

Example 1: Possible subspaces

| Dimension | Subspaces in $R^2$: | Subspaces in $R^3$: |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | The zero vector | The zero vector |

| 1 | Lines that pass through the origin | Lines that pass through the origin |

| 2 | All of $R^2$ | Planes that pass through the origin |

| 3 | - | All of $R^3$ |

Dimension of a subspace

The dimension of a subspace is always ≤ the dimension of the space it lives in.

Example 2: What does NOT qualify as a subspace? Think about a line that doesn’t pass through the origin - say, all points where $y = x + 1$. If we pick a vector on that line, like (0, 1), and we multiply it by the scalar 0, we get (0, 0) - which is NOT on the line $y = x + 1$. So that line isn’t closed under scalar multiplication, and therefore can’t be a subspace.

The distinction:

- While $y = x + 1$ is contained in ℝ² (every point on the line is in ℝ² - (0,1), (1,2), (2,3) etc.)

- It is NOT a subspace of ℝ² (doesn’t contain zero vector, not closed under operations)

- Therefore, it does not qualify as (does not form) a subspace.

The four fundamental subspaces of $A_{mxn}$

| Name | Dim | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Column Space | C(A)∈$R^m$ | Pivot columns of the original matrix |

| Null Space | N(A)∈$R^n$ | - Solve $Ax=0$, set free column variables to 1 respectively - # of free columns = dimension of null space |

| Row Space | C($A^T$)∈$R^n$ | Pivot rows |

| Left Null Space | N($A^T$)∈$R^m$ | Solve for y where $y^T.A=0$ |

Dimensions

For matrix A with dimensions $m$x$n$:

- $dim(C(A)) + dim(N(A)) = n$ (# of columns)

- $dim(C(A^T)) + dim(N(A^T)) = m$ (# of rows)

Orthogonal Subspaces

- $N(A) \bot C(A^T)$

- $N(A^T) \bot C(A)$

If the null space is {(0,0,0)} then (only consists of the zero vector),

- Dimension of null space = 0

- Number of free columns = 0

- All columns are pivot columns

Null space of A

If vector $\vec{v}$ is in the null space of matrix A, then A$\vec{v}=0$.

Complete Solution System of Linear Equations $x_{particular}$ : Set all free variables to 0, then solve $Ax=b$ (or $Rx=b$ where R is the echelon/reduced echelon form)

$x_{null space}$ : Set free columns to 1 and solve $Rx=0$. If there are more than one, set them respectively. For example, if there are two free variables (let’s say $x_2$ and $x_3$) first set $x_2 = 1$, $x_3 = 0$ and solve for $Rx=0$. Then set $x_2 = 0$, $x_3 = 1$ and solve for $Rx=0$. Two free variables mean there will be two special solutions.

A system’s solution set has three possibilities:

- unique solution

- infinite solutions

- no solution

If $det(A) = 0$ the system has either,

- no solution OR

- infinitely many solutions

Rank

- Matrix rank = # of pivots

- In a square matrix, if the rank < # of columns that means there are linearly dependent rows, thus the matrix is not invertible ($det(A) = 0$)

- The rank of A = # of independent rows = # of independent columns (very important)

Basis

Tip for Finding the Span

If we want to find that in the span of , we can just look at the rank of If the rank is smaller than the number of columns, can be expressed as a linear combination of the other vectors. In this case, the rank is <3 so yes, $\vec{v}$ is in the span of S.

Why use different bases?

- Simplification: Some problems become way easier in a different basis

- Example: In physics, choosing a basis aligned with forces makes calculations simpler

- Natural coordinates: Sometimes a problem has a natural coordinate system

- Example: If you’re studying oscillations, sine and cosine functions form a natural basis

- Revealing structure: Different bases can reveal hidden patterns in data

- Example: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in data science finds a basis that shows the most important directions in your data

Changing Basis

Solve for $\vec{w}$ where the basis A, B and $\vec{v}$ is known: $A.\vec{v} = B.\vec{w}$ You get $\vec{w}$ represented in basis B.

Orthogonality

- Two vectors are orthogonal if their dot product is 0.

- Two subspaces $V$ and $W$ of a vector space are orthogonal if every vector in $V$ is perpendicular to every vector in $W$.

- The null space $N(A)$ and the row space $C(A^T)$ are orthogonal subspaces of $R^n$.

- The left null space $N(A^T)$ and the column space $C(A)$ are orthogonal subspaces of $R^m$.

Projections

The projection of $b$ onto a subspace $S$ is the closest vector $p$ in $S$. A projection matrix $P$ is a symmetric matrix with $P^2=P$. The projection of is $b$ is given by $Pb$.

Projection onto a line

- x is a scalar.

Projection onto a Subspace

- x is a scalar.

Theorem: If $A$ has linearly independent columns then $A^TA$ is invertible.

Least Squares Approximation

- Solve $A^TAx = A^Tb$ where

and $y=c+mx$

Orthonormal Vectors

Vectors $q_1, …, q_n$ are orthonormal if $q_i^Tq_j=$

- 0 when $i\neq j$

- 1 when $i=j$

Assume A has orthonormal column, then we can find the projection matrix using

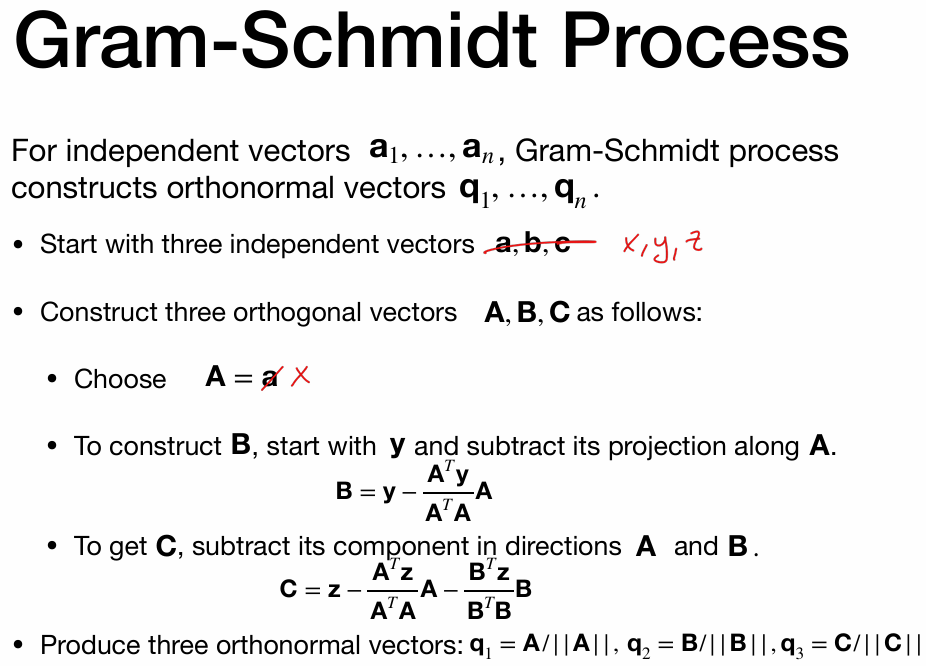

Gram-Schmidt Process

Eigenvectors & Eigenvalues

If, then $v$ is an eigenvector of A with eigenvalue $\lambda$. In other words, $Av$ lies in the same one-dimensional subspace as $\lambda v$.

Finding eigenvectors:

$(A - \lambda I)$ should have a non-trivial null space. Which means it is singular and $det(A - \lambda I)=0$.

Diagonalization

$AV = VΛ$ where $Λ$ is the diagonal eigenvalue matrix and $V$ is the eigenvector matrix.

Spectral Theorem

For a symmetric matrix $S$, the following diagonalization can be written:

where $Q$ is the orthonormal eigenvector matrix. i.e. eigenvectors of a real symmetric matrix are always perpendicular.

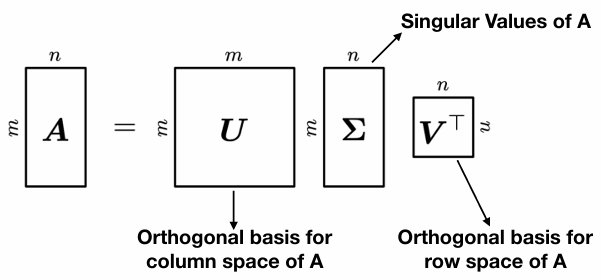

Singular Value Decomposition

Tip: SVD can be used for dimensionality reduction or compression.

or,

Once you find $V$ and $\varepsilon$, find $U$ by calculating $Av_i = \sigma_i u_i$ where $v$ and $u$ are eigenvectors of $V$ and $U$. $\sigma_i$ is the square root of eigenvalues obtained from $\varepsilon^2$.

Important note: $V$ and $U$ should have unit eigenvectors. Also, sort eigenvectors from in descending order of corresponding eigenvalues.